Boat Propeller School: Understanding Propeller Design, Performance, and Selection

Choosing the correct propeller is one of the most important factors in overall boat performance. The right propeller directly affects acceleration, top speed, fuel efficiency, engine load, handling, and long-term reliability.

This guide is designed to help boat owners understand how propeller selection works and why proper sizing and setup matter in real-world use. We will revisit the fundamentals and then dive deeper into how propeller form, fit, and function influence performance across different boating applications.

Propellers may appear simple at a glance, but their behavior is shaped by many interrelated design variables. Understanding these principles helps avoid common performance issues and protects propulsion systems over time.

Part 1: Propeller Terminology

Anyone who has shopped for a propeller has encountered terminology describing design and function. While diameter and pitch are often the first specifications discussed, efficient propeller performance depends on many additional factors. These include blade count, rake, cup, rotation, blade thickness, blade contour, skew, ventilation, cavitation, elevation, and angle of attack.

Each of these characteristics plays a role in how a propeller interacts with water and how effectively engine power is converted into forward motion.

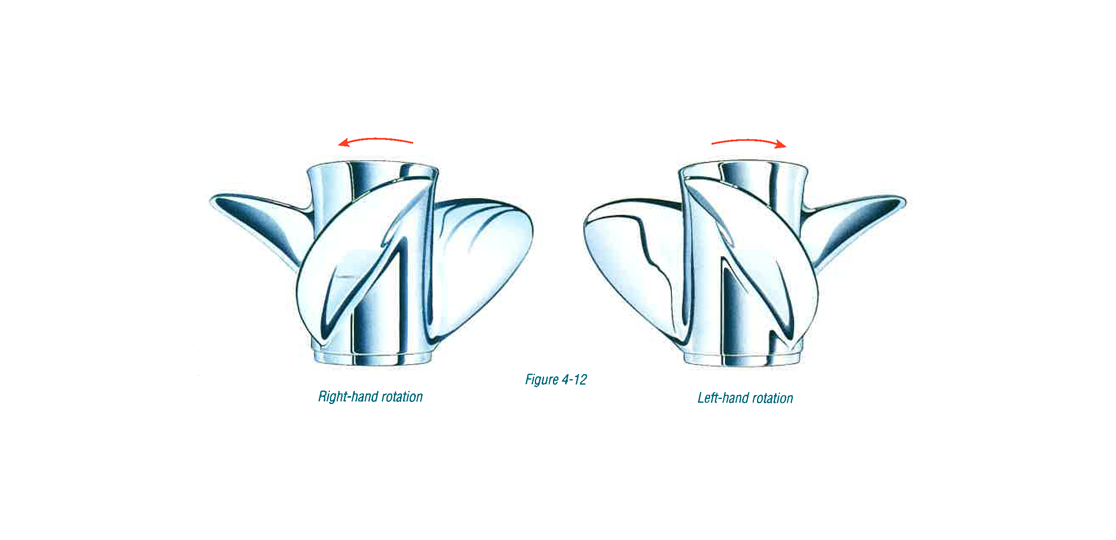

Rotation

Propellers are available in right-hand and left-hand rotation. Most single-engine outboard and sterndrive boats use right-hand rotation propellers, meaning the propeller spins clockwise when moving the boat forward. Left-hand rotation propellers spin counter-clockwise and are typically used in twin-engine applications to balance torque and improve handling.

In multi-engine setups, propeller rotation may be configured so the props turn toward each other or away from each other depending on hull design and performance goals.

Number of Blades

Most recreational boats use three-blade or four-blade propellers. Three-blade designs are efficient and typically provide good top-end speed with minimal drag. Four-blade propellers add blade surface area, which can improve acceleration, grip, and load carrying while further reducing vibration.

Additional blades are often used in performance or specialized applications where ventilation, hull design, or engine mounting height require more blade area to maintain efficiency.

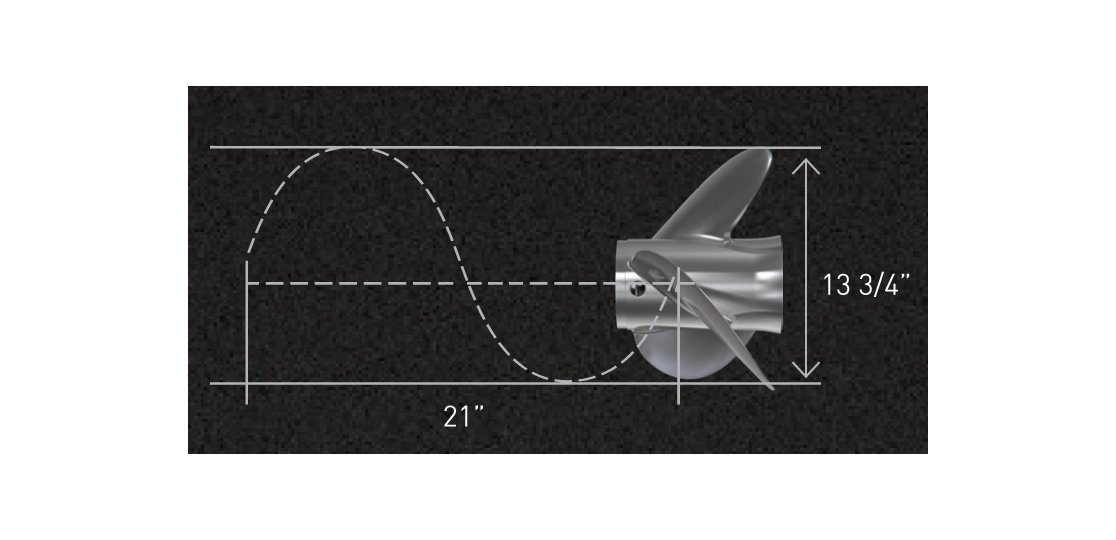

Diameter

Diameter is the distance across the circle created by the blade tips as the propeller rotates. Proper diameter selection depends on engine power, gear ratio, and propeller shaft speed.

Application also matters. Propellers that operate partially surfaced may require different diameter characteristics than fully submerged designs. In general, slower and heavier boats tend to use larger diameters, while faster boats use smaller diameters combined with different blade geometry.

Blade count and blade surface area influence diameter requirements as well. For the same pitch, a four-blade propeller will often have a slightly smaller diameter than a three-blade propeller.

Pitch

Pitch represents the theoretical distance a propeller would move forward in one revolution if it were traveling through a soft solid. Higher pitch reduces engine RPM, while lower pitch increases RPM.

Pitch is measured across the blade face and may vary slightly across the blade depending on design. Constant pitch means the blade pitch remains uniform from leading edge to trailing edge. Progressive pitch increases gradually across the blade, with the listed pitch representing an average value.

Proper pitch selection allows the engine to operate within its recommended RPM range. Too much pitch can cause the engine to lug, while too little pitch can cause excessive RPM. Both conditions increase engine stress and reduce long-term reliability.

Lower pitch propellers often improve acceleration and towing performance, while higher pitch propellers favor top-end speed and efficiency when properly matched.

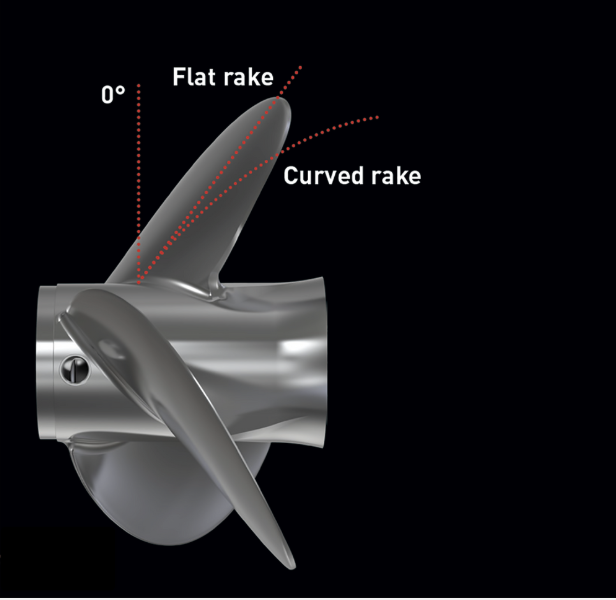

Part 2: Blade Rake

Blade rake refers to the angle of the blades relative to the propeller hub. Increased rake often helps lift the bow on lighter or faster boats, reducing hull drag and increasing speed. However, excessive bow lift can reduce stability on some hulls.

Hull design, center of gravity, engine height, and intended use all influence the ideal rake selection. Some boats benefit from higher rake, while others perform better with lower rake or cleaver-style designs.

Air-entrapment hulls, stepped hulls, and catamarans often rely on specific rake angles to maintain balance and efficiency as speed increases.

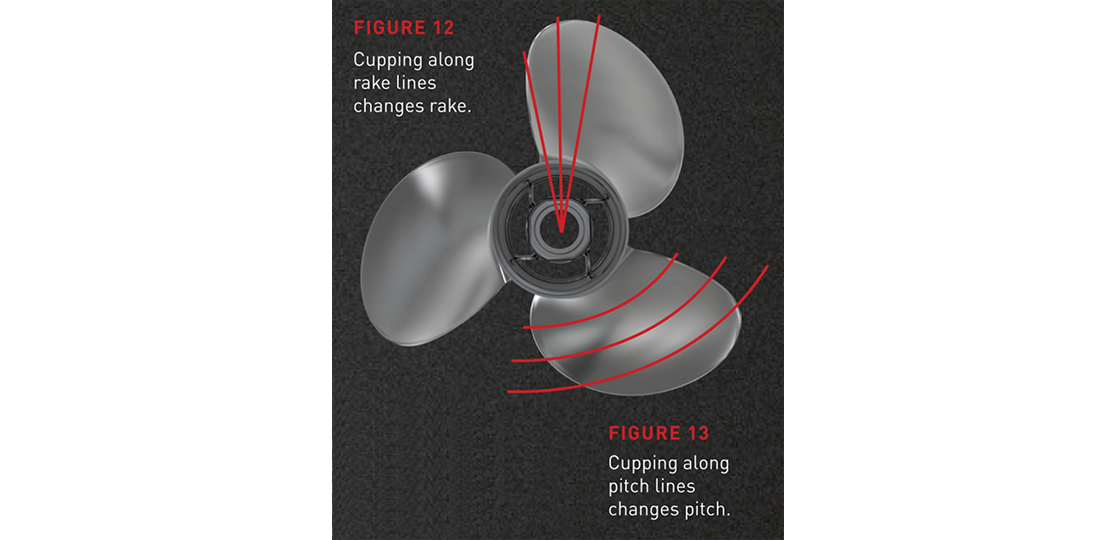

Part 3: Blade Cup

Blade cup is a curved lip near the trailing edge of the blade. Cupping influences grip, RPM, and resistance to ventilation or cavitation.

Adding cup generally reduces full-throttle engine RPM while improving bite. The location of the cup determines how it affects pitch, rake, and blade loading. Cupping can effectively increase pitch where it intersects pitch lines and can alter rake characteristics depending on placement.

Adjusting cup requires precision. Even small changes can significantly affect engine speed and overall performance.

Part 4: Blade Efficiency

Blade efficiency depends on how effectively the propeller converts engine power into thrust. Rotation direction, blade count, blade shape, and hull interaction all influence efficiency.

In twin-engine applications, counter-rotating propellers help balance torque and improve tracking. Some hulls benefit from additional stern lift, while others require reduced lift to reach optimal running attitude.

Performance hulls often operate in aerated water due to stepped or ventilated designs. Additional blade surface area helps maintain grip and reduce slip in these conditions.

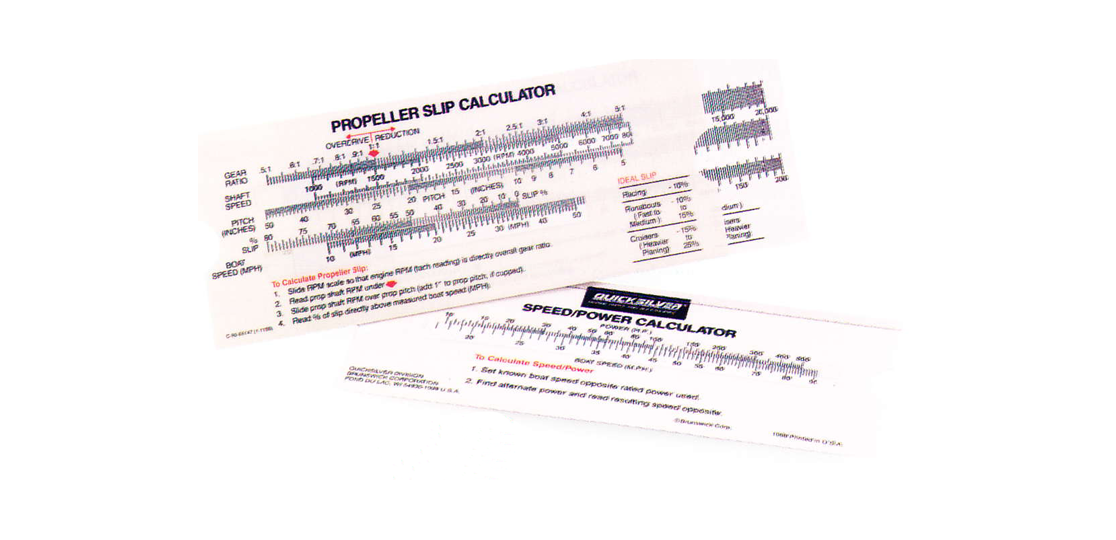

Part 5: Slip

Propeller blades function similarly to airplane wings. As blades rotate through water, pressure differences create lift that is translated into thrust.

Propeller slip is the difference between theoretical forward movement and actual movement through water. Some slip is necessary for thrust generation, but excessive slip reduces efficiency.

Efficient propeller setups typically operate within a reasonable slip range depending on hull design, speed, and application. Matching blade area, diameter, and pitch to engine output helps achieve the most effective angle of attack and optimal efficiency.

Part 6: Barrel Length

Barrel length affects stern lift and running attitude. Longer barrels tend to increase stern lift, which can help certain hulls plane more effectively. However, excessive stern lift can cause a boat to run too flat, reducing top-end speed.

Shorter barrels reduce stern lift and are often used in lightweight or high-performance applications. Barrel length is frequently adjusted when fine-tuning performance characteristics.

Part 7: Propeller Finishes

Propeller finish affects blade smoothness, thickness, and edge sharpness. Higher-finish propellers reduce drag and can improve efficiency and RPM.

Advanced finishes often feature thinner blades and sharper edges, which improve performance but require proper maintenance to retain effectiveness. These designs are typically used in performance applications where small gains matter.

Part 8: How to Reach Your Performance Goals

Propeller selection can be complex due to the wide variety of hull designs, engine configurations, and boating styles.

To simplify the process:

- Define clear performance goals. Consider what matters most: top-end speed, acceleration, fuel efficiency, handling, or load carrying.

- Establish baseline data. Verify tachometer accuracy and record RPM and speed under normal operating conditions.

- Evaluate the current propeller. Note blade count, diameter, pitch, barrel length, and condition.

Once goals and baseline data are established, propeller options can be narrowed to those best suited to the specific application. Small adjustments often produce meaningful improvements.

Supporting Long-Term Performance

The purpose of proper propeller selection extends beyond speed. The goal is balanced performance, engine protection, predictable handling, and long-term reliability.

Educated propeller choices reduce stress on propulsion systems and help boat owners get the most from their equipment across varying conditions.

For expert guidance on propeller evaluation, selection, and setup, contact Gregor’s Marine. Recommendations are based on real-world experience, manufacturer specifications, and practical performance testing.

Educational Attribution

This guide reflects long-standing industry propeller design principles developed through professional marine service experience and published manufacturer reference materials, including contributions from Mercury Racing.

Recent Posts

-

Boat Propeller School: Understanding Propeller Design, Performance, and Selection

Choosing the correct propeller is one of the most important factors in overall boat performance. The …Feb 4th 2026 -

Mercury Outboard Parts Lookup by Serial Number

The most accurate way to find the correct parts for a Mercury outboard is by using the engine’s seri …Jan 31st 2026 -

Marine Gear Lube Basics | SAE 90 vs 80W 90 for Lower Units

SAE 90 vs 80W 90 Marine Gear Lube SAE 90 and 80W 90 marine gear lubes can have similar viscosity at …Jan 31st 2026